Welcome

Parents & Caregivers – We understand this may be a very scary time for you and your child, and we are here to help guide you through this process.

Although, there are many similarities in the illness as it occurs in children and adults, there are some differences that are addressed here. Before reading about the illness in children specifically, we recommend reading these patient education pages first about pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma and pheo para genetics.

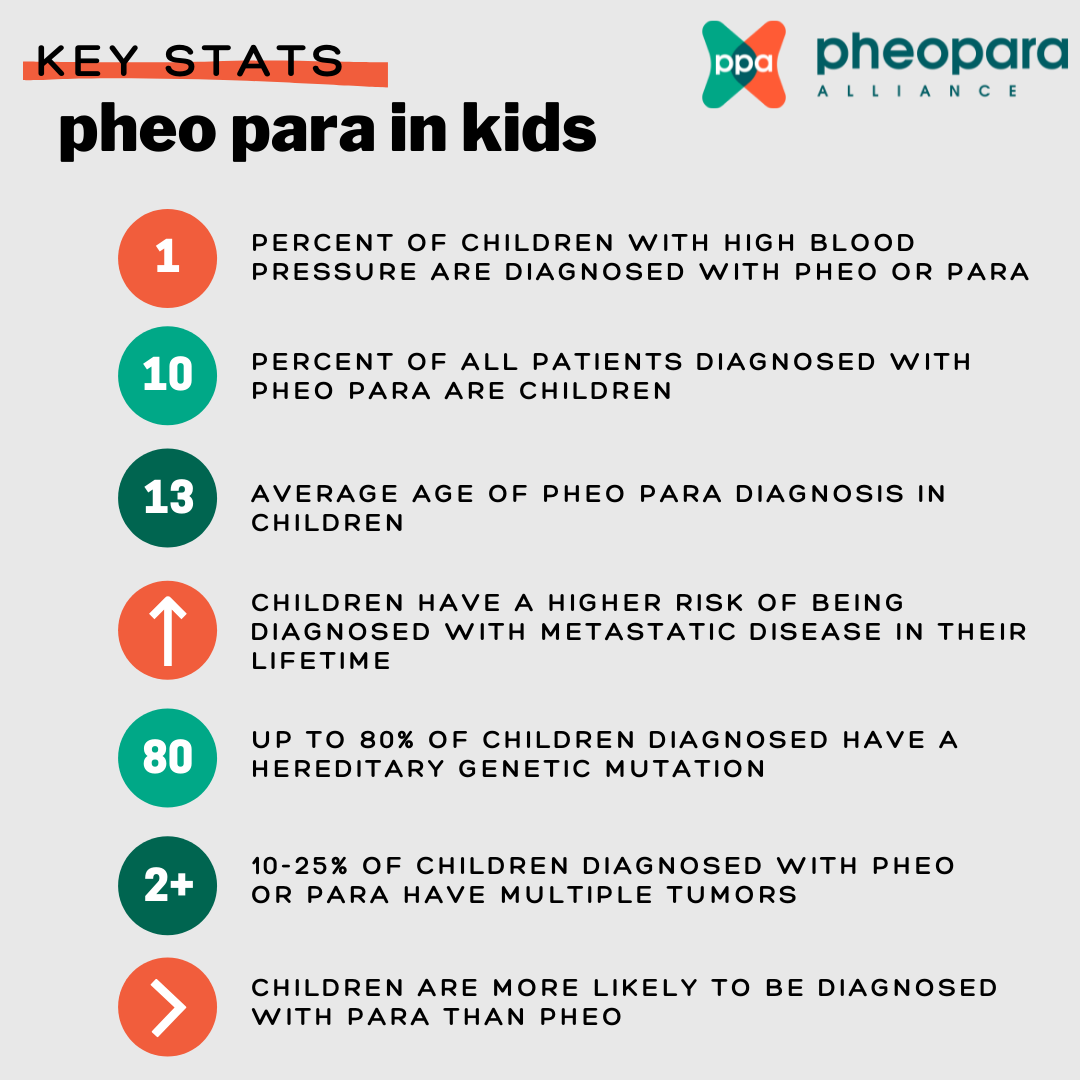

Pheo para is rare in adults and even rarer in children – approximately 2 children per million will be diagnosed annually. However, this rate may be underestimated due to undiagnosed cases, which is similar to that suspected in adults. Since pheo para is so rare, it is particularly important to be treated by an experienced pediatric pheo para medical team. The Pheo Para Alliance Center of Excellence program provides a directory of Centers of Excellence that provide top-notch multi-disciplinary pheo para care. You can also reach out to us directly regarding an experienced center near you at info@pheopara.org.

You can refer to this International Consensus Statement for Pediatric Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma and share it with your healthcare team.

All educational information is vetted by our Medical Advisory Board (MAB) who provides insight, scientific and clinical direction, and expertise to the Pheo Para Alliance. You can find out more information here. Also, check out this education webinar page addressing various pheo para topics, including a pediatric webinar citing relevant sources.

symptoms

Among all ages, signs and symptoms of pheo para are highly variable and dependent on tumor location, tumor size and whether it is secreting hormones or not. Some patients do not experience any symptoms.

Among children specifically, 70-90% present with hypertension, which is usually sustained (i.e., always having high blood pressure, as opposed only sometimes high). Signs and symptoms in children may include sweating, visual problems, weight loss, and nausea/vomiting. Other symptoms may include headache, neurologic symptoms and tachycardia (rapid heartbeat). Due to high catecholamines, children may also experience decreased school performance, behavioral problems and/or be diagnosed with ADD/ADHD.

You can find more info on signs and symptoms and what medication/food may aggravate symptoms on these pages: https://pheopara.org/education/pheochromocytoma & https://pheopara.org/education/paraganglioma under ‘symptoms’ tab.

genetics

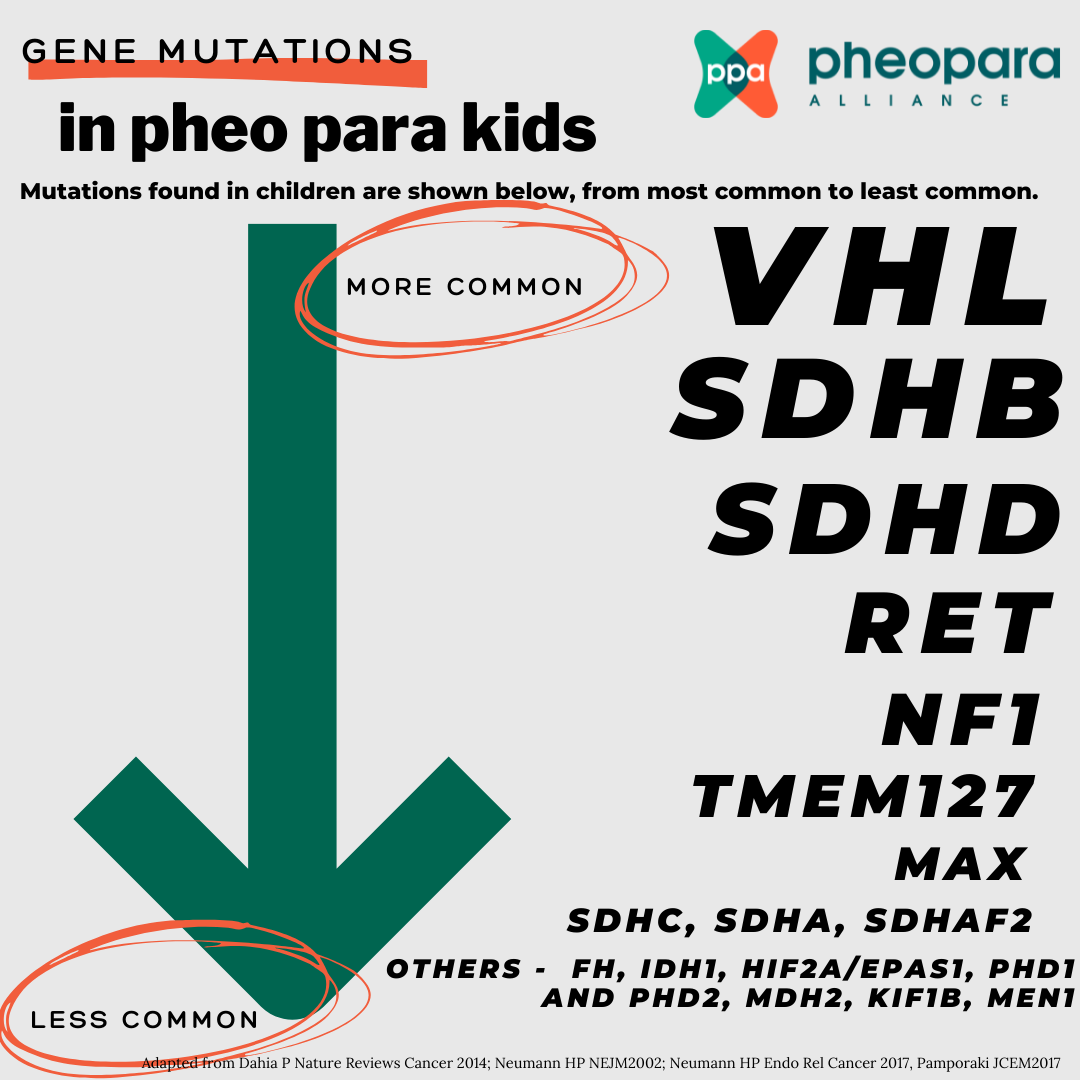

Up to 80% of cases diagnosed in children are the result of a specific gene mutation.

Thus, all children diagnosed with pheo or para should have genetic testing; family members will also need testing if a positive result in the child is found. Please read our genetics page for an overview of pheo para genetics.

For children who are diagnosed with a genetic mutation, regular monitoring is important to catch tumors early. Monitoring should be managed by an experienced medical team. Surveillance guidelines vary by gene, but typically start at ages 5-11 and include an annual blood or urine test (see pheo or para page) and periodic imaging such as MRI, CT and/or functional (nuclear medicine) imaging.

The vast majority of children diagnosed with pheo or para have VHL or SDHB. Mutations found in children are shown below, from most common to least common.

diagnosis

Methods for diagnosing pheo or para are the same in adults and children. The twenty-four hour urine and/or blood (plasma) tests are commonly used if pheo or para is suspected.

Both measure catecholamines and metanephrines (which are metabolites of catecholamines). Some researchers suggest blood (plasma) is more accurate. Either test can be used for kids; one or both may be preferred by your medical team or may be more convenient for you or your child.

In rare cases, a para, often those found in the head/neck, may not produce catecholamines, so no symptoms may be present. In this case, imaging (taking pictures of the inside of the body) is the preferred method for diagnosis.

Imaging is often used once biochemical tests indicate a pheo or para. Imaging will help to identify where, how many, and size of the tumor(s). In children whole body MRI is the preferred imaging to use first. CT scan or PET can be used on an individual basis.

Please refer to the ‘diagnosis’ section of this page for additional information on the 24-hour urine test, blood (plasma) test, types of imaging and other topics related to diagnosis.

treatment

Similar to adult patients, the preferred method of treatment for pheo and para is usually surgery to remove the tumor(s).

Overall, the method of surgical intervention for pediatric and adult patients is similar. Special alpha blocker medication is given to prepare for surgery. Surgery may be done laparoscopically or by making a larger incision, if necessary.

For bilateral pheochromocytoma, a bilateral adrenalectomy (removal of the adrenal gland on both sides) may be necessary to ensure no disease is left behind. In this case, adrenal insufficiency can be controlled with medication. In some patients with bilateral pheochromocytoma with a specific mutation such as VHL or RET, one adrenal is completely removed while as much tissue of the other adrenal is spared. In some patients this is technically not possible.

You can read more information on surgery and other treatments on the pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma page under the ‘treatment’ tab.

Watch this webinar on pheo para in kids from our 2022 Virtual Pheo Para Conference.

Surgery may not be possible because of advanced or metastatic disease. Several non-surgical treatment options may also be considered:

- Active observation. An experienced doctor may suggest only regular monitoring of the tumor(s) if they are not secreting catecholamines, there are no symptoms and the tumor(s) are stable (not growing). The active observation approach can be difficult for some people to deal with, but pheo and para tumors are often slow-growing or stable, and surgery, of any kind, is inherently risky.

- Targeted therapies, systemic chemotherapy

- External beam radiation, interventional radiology

- Targeted radiopharmaceutical (radionuclide) therapy such as 177Lu-DOTATATE (Lutathera, aka PRRT)

metastatic

It is highly recommended that patients with metastatic disease receive treatment from an experienced, multi-disciplinary pheo para team. Also, if your child has a genetic mutation, this may help to determine an appropriate course of treatment.

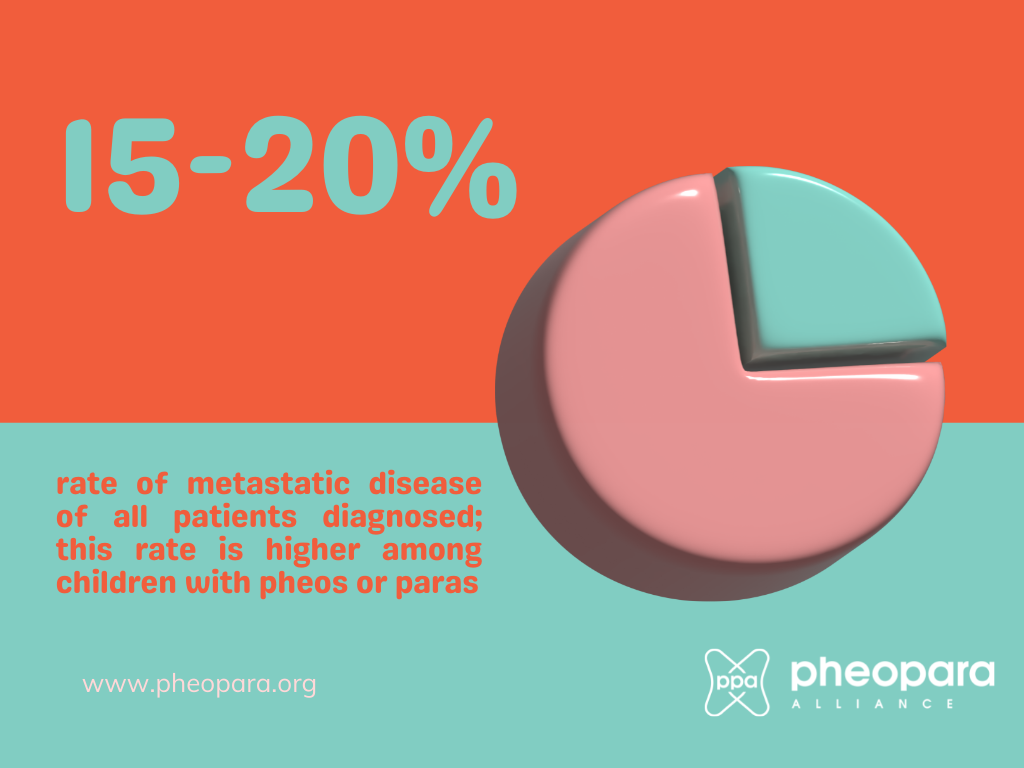

A pheo or para is defined as metastatic is if it has spread to a distant site, where pheos and paras are typically not found, such as the bone, liver or lungs. Currently, there is no cure for metastatic pheo or para. However, existing treatment options may reduce the tumor burden and prolong survival. Many patients live for decades with metastatic tumors.

The prognosis of metastatic pheo para is highly variable and is dependent upon the size of the primary tumor (tumors larger than 5 cm are more likely to metastasize, except in the case of SDHB, where tumors larger than 3 cm are more likely to metastasize) and genetic status. Paras that are originally in the head and neck are less likely to metastasize than paras that develop in other areas.

Some genetic mutations, such as SDHB, are more likely to develop metastatic para. You can read more about each genetic mutation and its prognosis on the genetics page.

Treatment of metastatic pheo or para can include the following options or a combination of a few of these:

- surgery

- Targeted therapies, systemic chemotherapy

- External beam radiation, interventional radiology

- Targeted radiopharmaceutical (radionuclide) therapy such as 177Lu-DOTATATE (Lutathera, aka PRRT)

Please see the ‘treatment’ portion of the pheo and para page for more information.

Clinical Trials

Participation in clinical trials, particularly for children with metastatic disease, is critical to providing options to patients and ultimately providing access to such treatments for all. Clinical Trials for children can be found by searching for ‘pheochromocytoma’ and ‘paraganglioma’ and ‘children’:

- Clinicaltrials.gov (U.S.)

- Health Canada’s Clinical Trial Database (Canada)

- EU Clinical Trials Register (Europe)

talking with kids

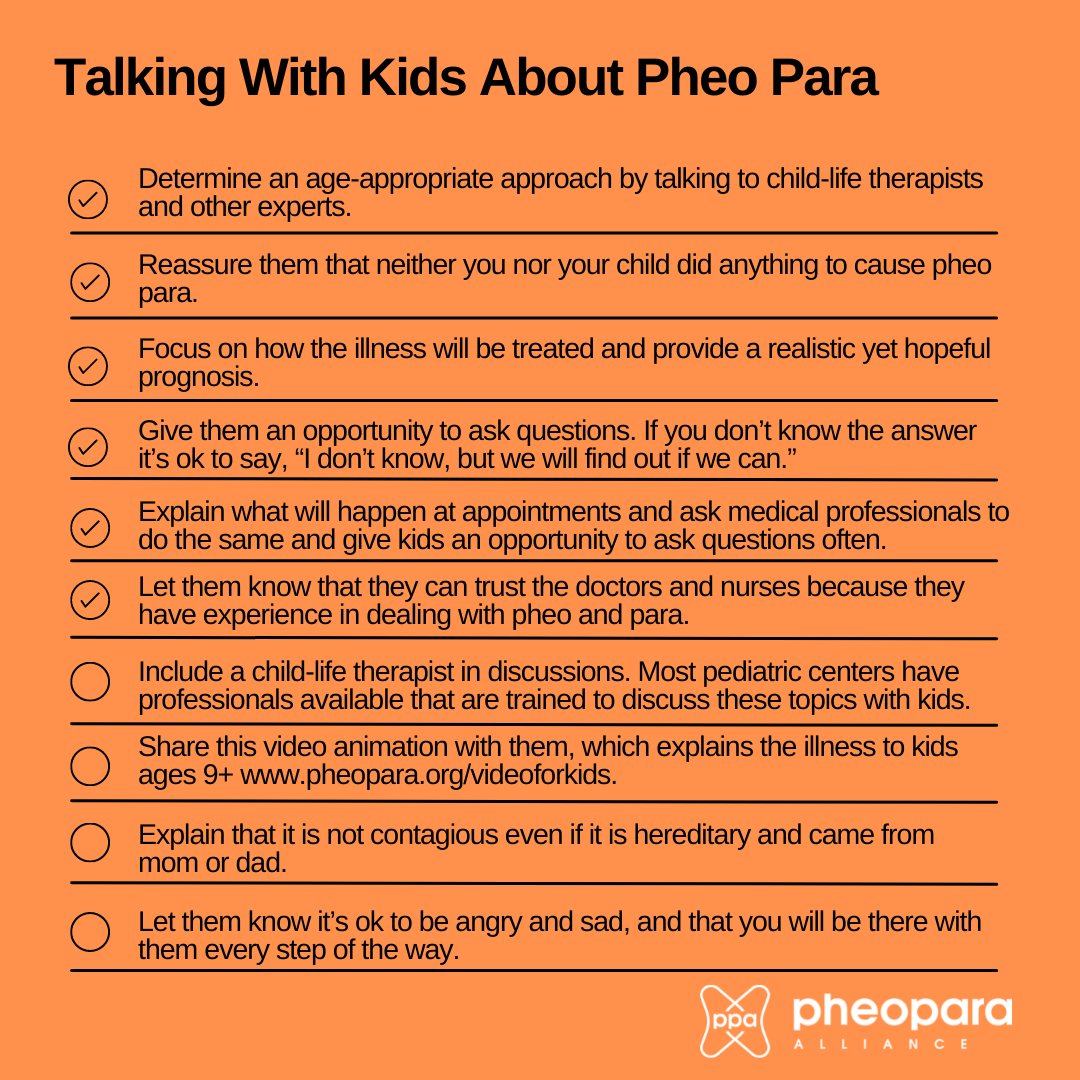

Speaking with your child about their pheo para or predisposition to developing the illness is important.

Children often sense that something is wrong, even when you do your best to shelter them from serious discussions with family and medical professionals. Talking to them about their illness consistently can help alleviate fears and help them feel supported and empowered.

This video animation explains the illness to kids 9+